Draft pod pairings - What round do you want to play against your friend?

Las Vegas, the perfect place to stay inside all day and play card games Source: Pixabay

Last weekend, a group of friends and I decided to make the several hour trek to Las Vegas to …. play Magic: The Gathering at MagicFest Las Vegas. We didn’t sign up for the main tournament, we just went around spending money on cards and fan paraphernalia and to sign up for some of the side tournaments. Generally, the side tournaments were structured as 8 person single elimination tournaments with a somewhat top heavy prize distribution.

| Wins | Tickets |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 20 |

| 2 | 200 |

| 3 | 400 |

One of those friends, Jon, and I decided to sign up for one of the side tournaments together. Another friend, Eric, didn’t want to risk playing with us and decided to sign up for a different event. Jon and I pondered about this, and figured that perhaps he just wanted to maximize our group winning potential (or just doesn’t like playing with us, who knows really) 1

Perhaps as a form of karmic justice, Jon and I ended up being paired in the first game. This guaranteed that one of us would be eliminated with 0 wins and thus leaving with 0 tickets. I quipped that this also guaranteed us at least one win and some tickets. Jon was understandably bummed that one of us would be leaving early and our potential for overall winnings was lessened. Eric was also nearby and remarked at the sad state of our luck before returning to his tournament to trounce on his opponents.

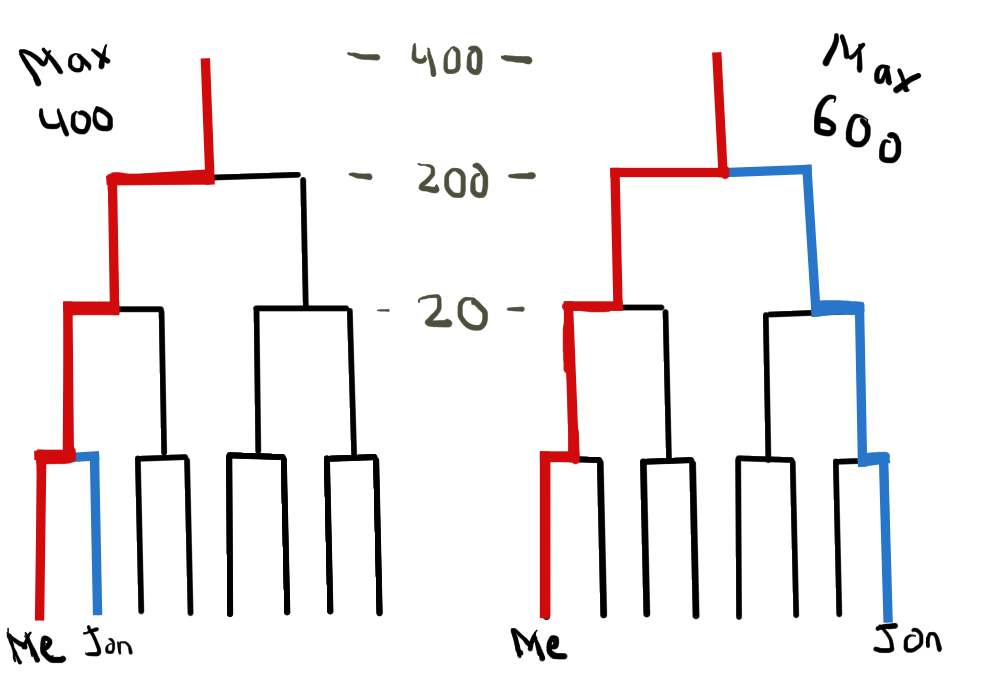

Comparing potential winnings between matching in the first round vs. matching in the final round

My intuition at the time was that our expected winnings was probably the same either way, and that perhaps we would even prefer to be matched with each other in the first round for consistency. But, Eric ended up winning several hundred tickets over the weekend. My victory over Jon in this game was the only win that either Jon or I got over the weekend. So perhaps Eric was right all along and we should all be taking advice from him.

But I don’t like focusing too much on what ended up happening. I prefer to console myself by reasoning about what my expected results should have been. So let’s try to answer the question:

Would we prefer to get matched in the first round or matched in the finals?

For my first stab at modeling the problem, I’ll assume that everyone at the convention is about the same skill level so that the probability of anyone winning a particular game is an even 50% for each player. Under these conditions, it doesn’t particularly matter when I face Jon (or even if face Jon at all!). The probability of me winning a game is a constant 50%.

Let’s first consider the expected value of just my winnings. The probability of me winning exactly 0, 1, 2, or 3 games is straightforward to calculate. We just have to multiply the probabilities of winning the desired amount of games and the probability of losing the last game if applicable.

| Wins | Tickets | Probability | Weighted Tickets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 20 | 5 | |

| 2 | 200 | 25 | |

| 3 | 400 | 50 | |

| Expected Value | 80 |

So the expected value of tickets I win is 80. Similarly, Jon’s expected value of tickets won is also 80. So what’s the expected value of the sum of the tickets won between ourselves if we’re in the same tournament? It turns out that the expectations just add due to the linearity of expectation.

So our expected total ticket is 1602. This works even though the amount of tickets we win individually aren’t independent! For example if we were to face each other in the first game, if I were to end up with 20 tickets (or any value more than 0), then Jon must have 0 tickets. Expected value sums don’t care about the individual terms being independent or not. That’s one of the fun properties I remember from college probability, and why my first intuition is that our seeding probably didn’t really matter in the first place.

Since the probabilities for winning a single game is constant, the overall expected value is the same whether we face each other in the first round or if we would only face each other in the final round. Therefore, we shouldn’t really care if we face each other in the first round. Don’t believe me? Just try out writing out all the possibilities and add it up. I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

But wait, Magic is a game of skill, right?! Otherwise, this game couldn’t have lasted over 25 years. If player skills vary such that the win probabilities are dependent on who’s playing, then the above calculations break down. If Jon and I would beat everyone else at the convention, then we would prefer to not face each other until the finals so we can guarantee getting 600 tickets total. Conversely, if Jon and I can’t beat anyone else at the convention, then we would instead prefer to match with each other in the first game so that we can walk away with 20 tickets instead of nothing.

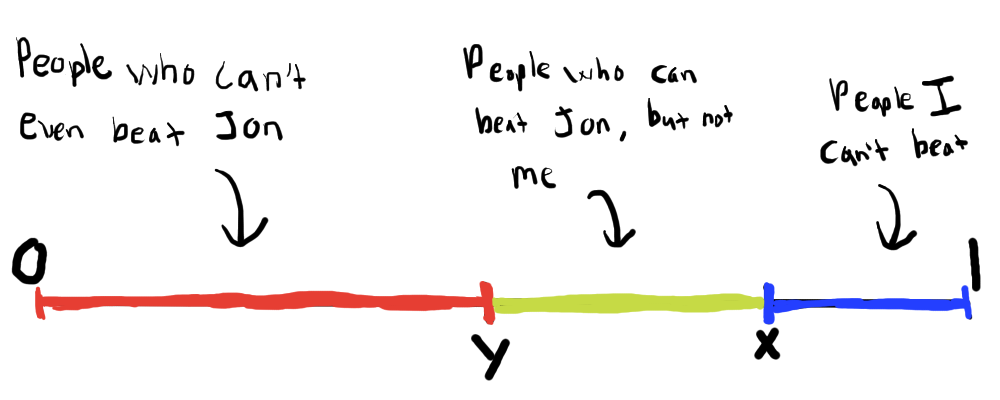

Let’s assume then that Magic is a game of pure skill and that all players can be ordered in a line (the skill spectrum) such that players will beat everyone else behind them in the line 100% of the time. We can then represent player skill as the percentage of players they would beat in a game of magic. The tournament is then seeded with Jon, I, and 6 other players chosen independently uniformly randomly from the skill spectrum.

Let be my skill and be Jon’s skill. For the sake of not duplicating logic, let’s also assume that . I did beat Jon after all in this tournament. However, similar logic follows in the case of .

I want to emphasize that and are constants and that the only source of randomness is the selection of the 6 other players from the skill spectrum. Given the selection of the 6 other players and the tournament bracket, the results of the tournament are deterministic.

In this setting, the probability of winning does change when and if I face Jon. So let’s first consider the case where we match up in the first round. I am guaranteed to win the first round. Then I have face the winner of the 2 random people. If this was just a random person chosen from the skill spectrum, the probability that this person’s skill is lower than mine is $x$. However, this player beat another random player and therefore had skill higher than another random player.

If the 2 players have skill ratings and respectively, then the player who wins has skill rating . What’s the probability that is less than some value ? This only occurs if and only if both and are less than . Since the selection of individual players is independent, that’s just the product of and individually being less than .

The probability that I win is the probability that the value is than my skill rating , which is just . Similarly, if I make it to the third game, my opponent would be the best of 4 random players. The probability of being lower than my skill rating is .

Overall, my expected value for tickets in the case of being matched with Jon in the first round is

| Wins | Tickets | Probability | Weighted Tickets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | ||

| 2 | 200 | ||

| 3 | 400 | ||

| Expected Value |

Since Jon is guaranteed is to lose the first game and get 0 tickets, this is our overall expected value of total tickets.

Now let’s consider the case where we would only face each other in the finals. In the first game, I’m paired with a random player, which we know that I can beat with probability . For the second game, I would need to beat the better of 2 random players and win with probability . For the third game, I would need to beat the best of 3 random players and Jon.

Since because I’m better than Jon, the probability that I can beat this player in the finals is .

My expected value of tickets in the case of meeting Jon only possibly in the finals is:

| Wins | Tickets | Probability | Weighted Tickets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 20 | ||

| 2 | 200 | ||

| 3 | 400 | ||

| Expected Value |

Similarly, in the first round, Jon would have to beat a random player with probability . Then if he reaches the second round, he needs to beat the better of 2 random players with probability . If Jon wins 2 rounds, then he would have to face me or someone who is better than me, so he has no chance of winning the final round. Jon’s expected tickets in the case he doesn’t have to face me until the finals is:

| Wins | Tickets | Probability | Weighted Tickets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 20 | ||

| 2 | 200 | ||

| Expected Value |

With linearity of expectation, we can just add these expected values to get the expected total

So when do we want to be matched up only in the final round? That’s when the expected value of tickets of being matched only in the final round exceeds the expected value of tickets of being matched in the first round.

The left side is the expected value of tickets that Jon gets trying to win tickets on his own. The right side represents the marginal expected tickets I get if I get a free win from Jon compared to if I had to beat a random person in the first game3. So we would prefer to not be matched with each other if we believe that Jon would get more tickets by himself than we would if he gives me a free win.

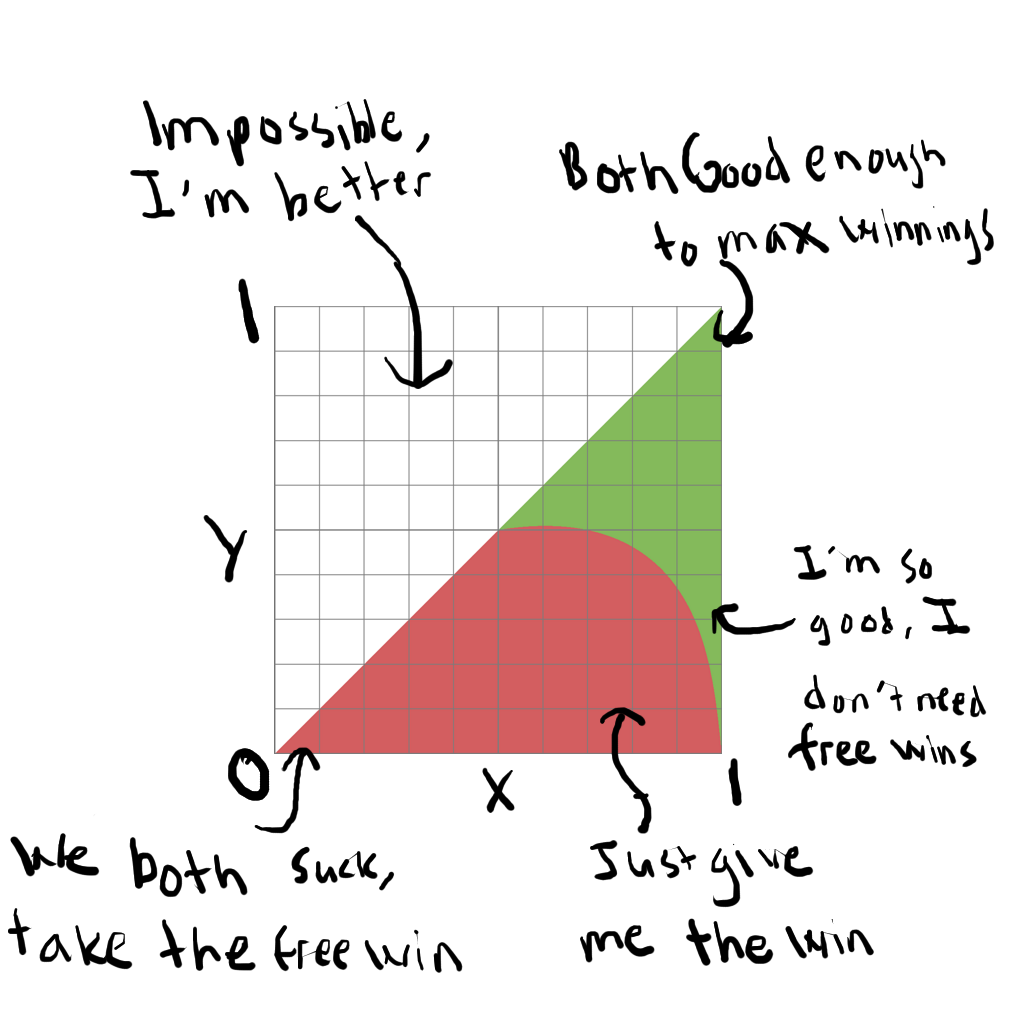

We can graph over the valid values for and to get a better understanding of when this happens

Plotting preferences over (my skill rating) and (Jon’s skill rating). Red is the area where we prefer to be matched in the first round. Green is the area where we prefer to be matched in the final round. The plot only covers half the space since the values are only valid for . For , just imagine flipping the figure over the diagonal.

As expected, around , we would prefer to match at the final round to maximize winnings. Around we would prefer to match up in the first round to take the free win. What was interesting to me was the behavior when Jon is a below average player. There’s a large area where even if I was pretty good, I would still prefer to match with Jon in the first round because we get more tickets overall if I get a free win compared to leaving Jon to try to win tickets on his own. It’s only when I get closer to elite skill levels that I don’t get as much value taking the free win from Jon than Jon would get winning tickets on the other side of the bracket. However, when Jon is an above average player, also implying that I am an above average player as well, we would prefer to split up in the bracket the vast majority of the time.

In conclusion, if you and a friend sign up for a MagicFest side tournament to get as much tickets as possible and both of you are above average players, then you would prefer to get seeded in separate sides of the tournament bracket. Otherwise, if either of you are below average players, then it’s likely you want to pair up in the first round instead! Since everyone believes they’re an above average player, this means that everyone should want to match up on opposite sides of the bracket.

Now I’m ignoring the fact that Magic isn’t quite a game of pure skill, so there’s room for allowing for differing player skill affecting win probabilities, which would allow Jon to win games against me and perhaps change the overall calculus. But that’s an exercise for perhaps another day.

Links:

Footnotes:

-

Eric would like to put for the record that he just wants to play with people he doesn’t already know. He just likes testing himself against unknown players and decks. ↩

-

I could have also reached this result by noting that the total tickets won in the tournament is 640 and that each of the 8 participants have equal probabilities of reaching any result. So the expected value of winnings per participant is . But laying out the win count probabilities extends better to the rest of this writing. ↩

-

The terms disappears because it shows up in both sides. It’s related to the marginal additional tickets of me making to and playing the final game. Regardless of whether I face Jon in the first game or in the finals, I end up having to be better than 6 random people to get to and win in the finals. ↩